The Supreme Court lays down a precedent on Internet platforms: HomeAway does not have to verify whether its vacation rental listings are lawful

Cristina Mesa Sánchez, partner at Garrigues Intellectual Property Department

Internet platforms were waiting with baited breath to know what position the Supreme Court (Chamber Three) would take in its judgment 1818/2020 of December 30, 2020, with the court ultimately confirming that the vacation rental marketplace HomeAway is an intermediary provider of information society services and therefore cannot be required to monitor or be liable for the activity of its users, namely the property owners or managers that list their vacation rentals on its site. The Supreme Court’s stance is in lock step with the Court of Justice of the European Union, but strays from the reforms introduced by the European Commission in its proposed Digital Services Act, and that will surely lead to some controversy.

The Supreme Court’s findings in the HomeAway case reflect the principles repeatedly upheld by the Court of Justice of the European Union as regards the liability of Internet intermediaries:

- The only information society service providers that can benefit from the exemption from liability as regards the underlying service are intermediary providers, namely those that play a passive role in the underlying service provided on their platforms (e.g., vacation rentals, transport, retail sales, etc.).

- In particular, intermediary providers of hosting services are not liable for any illegal content uploaded by their users unless they have actual knowledge of such illegal content.

- What is considered “actual knowledge”? Where a court or administrative order has deemed the content to be illegal or, failing that, where the provider has been informed of the content and the content is “manifestly illegal”.

- In all cases, intermediary service providers cannot be subject to a general monitoring obligation to detect any illegal content.

Background

The roots of the issue lie with a decision by the Directorate-General of Tourism of Catalonia (DGTC) ordering HomeAway to block from its website all the listings of Catalonia-based tourism establishments that did not include a Catalonia Tourism Registry number. In other words, the DGTC was asking HomeAway to actively control the activity of its users to determine whether or not they were complying with tourism industry regulations. Both the Catalonia Regional Government Secretary for Business and Competition and the Catalonia High Court (TSJ) upheld the DGTC’s decision.

In particular, the Catalonia High Court’s judgment considered HomeAway’s activity to go beyond mere intermediation of services and to instead be at the “core of the vacation home and property rental business, given that it organizes the information however it wants, advertises in the terms it chooses, manages reservations and dominates the transaction by controlling the economic flow, that is, by requiring that payments go through it”.

The Supreme Court admitted the cassation appeal lodged by HomeAway for consideration, understanding that the issue at play was of cassational interest in order to set future case law on the legal treatment for information society service providers and their liability.

It is important to note that the parties had no dispute about what HomeAway’s activity is:

- Posting third-party accommodations on its website;

- Managing the reservations received by renters and forwarding them to the property owners;

- Receiving the amount of the rent plus a security deposit, through a payment platform;

- Temporarily holding deposits; and

- Replying to inquiries received from renters.

For these services, property owners pay HomeAway an annual fixed fee of €199 plus 3% of reservations, and renters pay it an additional 6% of the rental price.

Consequently, the Supreme Court did not assess the facts, but rather HomeAway’s legal characterization to determine whether HomeAway is a mere intermediary provider of information society services or whether it is a provider of accommodation services. The distinction is not trivial, given that it determines, for example, which rules of liability the platform will be held to for the content its users post on it. Let’s take a look.

Supreme Court analysis

1. What criteria should be taken into account to determine the nature of the services offered by an information society service provider?

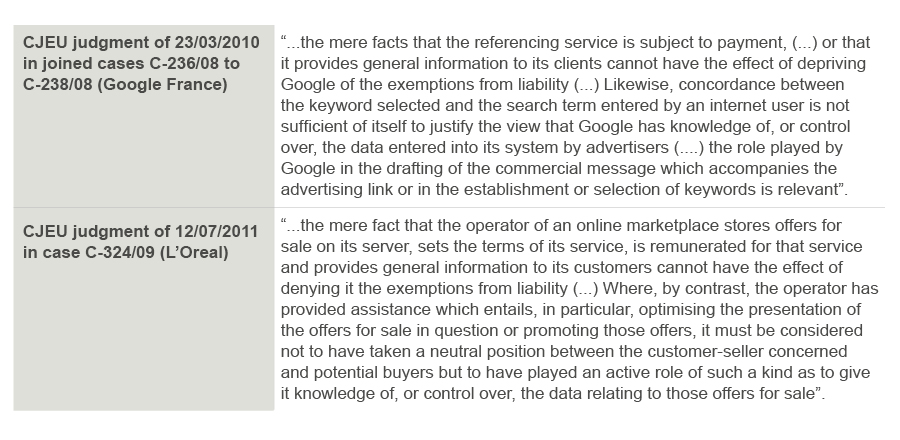

The Supreme Court approached its analysis by first looking at two key European Union judgments regarding liability of intermediaries: the Google France case and the L’Oreal case. Both judgments focused on identifying the factors that should be taken into account to determine whether an information society service provider is acting as a mere intermediary or whether, in contrast, it participates in the underlying service offered on its platform:

Based on the foregoing, the court concluded that whether or not an information society service provider is an intermediary depends on whether it plays an active role in the underlying service, in this case, vacation rentals. The CJEU has consistently used this litmus test (active role vs. passive role) to date, making this the starting point for any analysis to determine the extent of a provider’s liability regime.

Looking particularly at the industry in question (vacation rentals), the Supreme Court cited the recent CJEU judgment in the Airbnb Ireland case, which we analyzed here. The CJEU cited three key factors for determining whether an information society service provider plays an active role in the underlying service:

- whether the platform’s value proposition is merely ancillary to the underlying accommodation service;

- whether the platform’s services are essential for the underlying service to be provided;

- whether the platform has effective control over the underlying vacation rental business.

Based on these factors, the Supreme Court concluded that HomeAway is indeed an intermediary since:

- HomeAway’s activity can be separated from the service provided by the homeowners that list their vacation rentals. HomeAway’s value proposition is not the accommodation in and of itself but rather the creation of an accommodation database and the tools that facilitate searches (comparison tools, filters, etc.) as well as the homeowner-renter transactions.

- Although HomeAway’s activity, as a platform, is very relevant in the information society, it is not essential, since these services can be carried out through other channels (such as traditional travel agencies, classified ads, etc.)

- Nothing indicates that HomeAway has any control whatsoever over the rental prices set by homeowners.

- None of the additional services offered by HomeAway (such as reservation management, payment gateway, queries, commissions, etc.) detracts from its role as a mere intermediary, because these additional services do not constitute, in and of themselves, the ultimate objective of the property owners and renters, but rather “they are ancillary to offering or using the intermediary service rendered by the platform and forming the core of its activity, namely to put property owners and renters into contact with one another”.

Based on the interpretation criteria set by the CJEU in the Google France, L’Oreal and Airbnb Ireland cases, it should be concluded that HomeAway plays a passive role in the underlying vacation rental service offered by its users and, therefore, that its activity is that of an intermediary provider.

2. Are intermediaries required to comply with industry regulations applicable to the underlying service?

No. The regulations applying to the vacation rental industry are mandatory for the homeowners that list their properties through HomeAway, as these homeowners define and control the offer, but not for the platform, which merely facilitates the transactions between its users.

To reach this conclusion, the Supreme Court approached its analysis by first determining the nature of the intermediary services rendered by HomeAway, defining them as hosting services. Accordingly, the rules on liability established in article 16 of the Information Society Services Law (LSSI) apply, according to which if the intermediary information society service provider does not have actual knowledge that information hosted is illegal, it is not liable for such information or for its illegal nature.

The Supreme Court acknowledges that property owners that do not include their tourism registration number in their listings are clearly infringing the applicable regulations. However, what must be clarified is whether HomeAway has actual knowledge of this infringement, which would trigger its obligation to remove the infringing listings (or to prevent users from viewing such listings). The court considered that HomeAway does not gain actual knowledge of the infringement simply by hosting the listings posted by its users:

“Indeed, none of the circumstances cited in article 16.1.b) of Law 34/2002 to evidence such actual knowledge are present in this case. There is no declaration from the competent body of the Catalonian authority that certain listings were unlawful for having failed to include the registration number and ordering the removal of such listings”.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court also takes into account that, in the absence of a court or administrative order, intermediary providers would only gain actual knowledge of the illegal nature of a given content if the contents were “manifestly illegal”:

“(...) it must be borne in mind that, as the appellant argues and as stated in the lower court’s judgment, its website not only features tourism rental listings that, pursuant to Catalan Law 13/2002 are required to feature a registration number, but also other types of accommodation that are not subject to this obligation. Given this circumstance and the nature of the intermediary services, which are merely ancillary to the underlying activity (in the terms already set by the Court of Justice of the European Union), the omission of certain administrative requirements cannot be considered manifestly illegal and an automatic trigger requiring the information service society provider to remove the illegal listings.

Consequently, information society service providers that merely act as intermediaries of the underlying service are not required to comply with industry-specific regulations, which makes perfect sense when bearing in mind that they do not - and should not - have any control over that service.

3. Does the obligation to control whether homeowners offering vacation rentals comply with industry-specific regulations constitute a monitoring obligation that would breach article 15 of the e-Commerce Directive?

Yes. The Supreme Court categorically concludes that it is not appropriate to impose a general monitoring obligation on intermediaries, as doing so is expressly prohibited under article 15 of the e-Commerce Directive, which states as follows: “Member States shall not impose a general obligation on providers (...) to monitor the information which they transmit or store, nor a general obligation actively to seek facts or circumstances indicating illegal activity”.

Based on the foregoing, the Supreme Court concluded that HomeAway cannot be required to monitor or filter its users’ listings in order to assess whether or not they are legal:

“... [the] administrative order underpinning the dispute... is a general order that would oblige the service provider to examine the content of its listings, to determine which are for tourism apartments and to delete those that do not include a registration number. Such an obligation would directly contravene article 15 of Directive 2000/31/EC and be incompatible with the legal treatment for hosting information society service providers. In essence, it would be tantamount to tasking them with inspecting and controlling content, a function that falls to the competent authority. If, in exercising its functions, the competent authority verifies such infringements by parties subject to the regulations (the property owners or the advertisers), it could declare the content to be illegal and require the service provider to remove the listing or to block access thereto.”

Consequently, it must be understood that HomeAway cannot be obligated to monitor its users’ activity in order to seek out potential administrative infringements. Nevertheless, as the Supreme Court noted, the service provider could be ordered to cooperate if the competent authority identifies an infringement and asks the service provider to remove specific, duly identified listings.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court laid down this legal precedent in the midst of a debate on the European Commission’s proposed Digital Services Act (see our analysis here). For many, the text proposed by the Commission calls into question the liability rules for online platforms, particularly very large platforms, introducing due diligence obligations to attempt to avoid the distribution of illegal internet content. Let the controversy begin.