How to hire an influencer that doesn’t exist

Cristina Mesa (senior associate at Intellectual Property and Fashion Law Practices and Álvaro de la Cueva (partner at Tax department).

Just when it seemed that the rules and regulations on contracting influencers were getting clearer, along came Lil Miquela (@lilmiquela). She has over a million followers or "miquelitas" on Instagram, and has contracts with brands like Prada, Chanel and Supreme. Not to mention several hits on Spotify, and the fact that she strongly supports “Black Lives Matter". A force to be reckoned with.

What is special about this 19-year-old influencer of Spanish-Brazilian origin is that not a single one of her freckles is genuine. No one knows exactly how Lil Miquela, the first computer-generated influencer, came about. Nothing is known about who created her, or who manages her lifestyle on-line, or who negotiates her contracts. This particular influencer has followed in the footsteps of other virtual personalities like the British band Gorillaz or the pop idol Hatsune Miku.

And so the first conundrum that presents itself in this scenario is how do we contract an influencer if they do not exist? Below you will find an outline of the main legal aspects to be considered when contracting the services of a virtual influencer.

Is it possible to protect a virtual influencer's appearance?

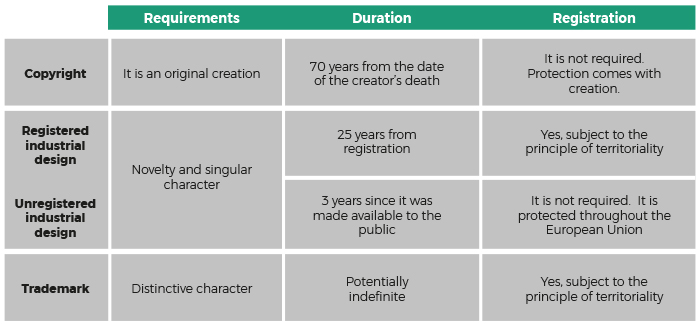

Without question. There are several instruments available for this purpose, such as copyright, industrial drawing, whether registered or unregistered, and sometimes, trademark law. The following table summarizes the main features of each protective measure:

From the foregoing, it is clear that virtual influencers are protected in the same way as any animated character, just like those of Disney, Pixar or Nickelodeon, companies that have character merchandising down to a fine art.

What is more, these channels are cumulative, and so, provided that the prerequisites are fulfilled, there is nothing to stop the same character being simultaneously protected by copyright and trademark regulations.

Do we need to obtain the influencer's image rights?

No. Image rights only apply to natural persons, and therefore they only need to be considered when contracting traditional influencers. In the case of virtual influencers, all we have to do is obtain the appropriate intellectual and/or industrial property rights.

However, some campaigns are mixed, in that they combine both real and virtual characters, in which case the image rights of the natural persons involved would need to be obtained.

Who do we approach in order to contract the services of a virtual influencer?

The owner of the rights or the company to which they have been licensed. It may well be that the virtual influencer is the company's own creation, in which case the creative process should be taken into account. If the influencer was generated by the company's own employees, there is a presumption of ownership in its favor, although it would be advisable to review the intellectual property clauses entered into with the employees. Conversely, if a third party was commissioned to generate the influencer, we would have to be extremely careful to ensure that we have obtained all the intellectual and industrial property rights required for its exploitation worldwide.

What type of agreement would we need?

The contractual structure should be two-pronged. On one hand, it should regulate the provision of services, which in this case would be aimed at the team that created the influencer. On the other, it should ensure effective assignment of all the intellectual and industrial property rights needed in order to run the campaigns:

- Service agreement. Firstly, we would need to contract the creation of the works that we plan to disseminate. For example, the creation of 3D illustrations, in which the influencer displays the collections that we want to disseminate on Instagram or Facebook. Another example would be videos that we wish to upload on YouTube. These are authentic productions which may involve the input of script writers, illustrators, animators, etc.

- Assignment of rights agreement. This type of contract would ensure that we obtain all the intellectual and industrial property rights required for our proposed uses. For example, promoting campaigns on our own social networks, press, and corporate websites and so on.

In any case, it would be necessary to specify in as much detail as possible exactly what actions the influencer would be asked to take. The degree of creative freedom that we allow the scriptwriters and illustrators is another matter, although we would recommend that approval of the final result be reserved in all cases.

What needs to be considered when contracting a virtual influencer?

From a legal perspective, there are specific clauses which are to be carefully considered in this type of agreement. For example:

- Exclusivity. The possibility of obtaining exclusive rights in a particular sector, or failing this, the possibility of excluding our most direct competitors. However, exclusivity tends to have quite a significant budgetary impact.

- Control. As in the case of traditional influencers, the possibilities of controlling the final result should be analyzed on a case-by-case basis. If we are contracting an influencer because of his/her persona, there is not much point in telling that character how to behave. Notwithstanding this fact, get-out clauses should be included for cases in which the influencer's conduct, or rather their script writers’, clashes with brand values (e.g. political statements, prohibited substance use, behavior inappropriate for children and so on.)

- Followers. The contractual duration should also be subject to the continuance of a specific number of followers on social networks. Mechanisms may also be established for checking their quality and avoiding fraudulent practices.

- Confidentiality. It is highly likely that the influencer’s owners will wish to maintain the confidentiality of some aspects of their contracting, such as, for example, the contractual price paid, or in the case of Lil Miquela, the name of her creator.

- Advertising. Finally, we also need to be sure that the campaigns contracted comply with advertising standards and requirements, such as, for example, the need to make it clear to consumers that this was an agreed recommendation. The virtual nature of the influencer does not mean that we are not required to clarify that this is an advertising feature (#advertising or #ad) unless it is obvious that this is advertising material.

Can I recreate the appearance of a virtual influencer without the author's permission?

No! Technically it is very easy, but if you do so, you will most likely be infringing third party intellectual and/or industrial property rights.

In Spain, we have a significant precedent regarding unauthorized use in the case of the Lara Croft character on the front cover of Interviu magazine, (Judgment of the Provincial Appellate Court of Barcelona of 28 May 2003). Not only does the judgment make an award for property damages incurred by the Lara Croft creators, but it also includes moral damages incurred as a result of the character being "stripped naked " without their authorization.

"The report should be considered as a whole which resulted in "infringement of the moral right of the claimant, by displaying altered drawings of the audiovisual game character, together with the aforementioned texts and photographs of the model in the manner described, creating an association between Lara Croft and a sexualized image that does not correspond to her personality, and which damages or violates those rights, and in addition infringes the property rights referred to previously"

It is important to bear in mind that Spain has no equivalent to the US fair use doctrine, and that any use of a third party's work, except for a small number of exceptions, shall always require their consent. As such, it cannot be alleged that there was no commercial intent when attempting to justify any unauthorized use of works protected by copyright.

Are there any particular taxation aspects to consider?

Basically, in the case of contracts entered into with the right holders or licensees of rights, it is their legal personality that needs to be considered. In the case of a natural person, personal income tax (IRPF) will normally need to be withheld on the amounts paid (either as service agreements or as intellectual or industrial property rights) and VAT will also be payable.

In the case of a legal person, withholding tax is only applicable if there is an assignment of image rights (which would only apply in the case of mixed campaigns because virtual influencers cannot hold image rights as they are not natural persons) or if the agreement includes both the provision of services and the assignment of intellectual or industrial property rights. This is in addition, of course, to VAT.

These issues may become more complicated when the owner or licensee in question is not a tax resident in Spain, as this can have considerable repercussions in relation to both withholding tax on the payments and VAT. As a general rule, this will all depend on the country where the owner or licensee is resident, on whether the agreement concerns the provision of services or assignment of the rights in question, or if the campaign will have effects in Spain.

All these circumstances are difficult to assess, and will require a preliminary case-by-case analysis, because normally, the company that owns the rights will be reluctant to accept a reduction in the payment it receives owing to the application of a Spanish tax, and will want to receive the full amount, therefore demanding that the Spanish company assume the cost of these tax payments itself.